Basilica Soundscape’s Creative, Independent Brandon Stosuy

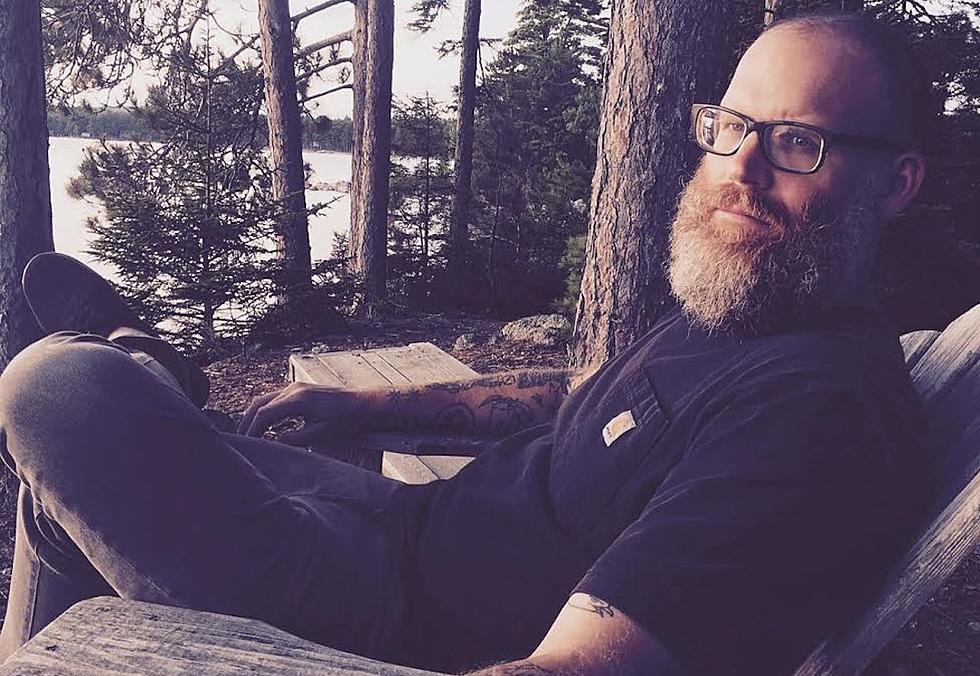

The perception of Brandon Stosuy is in stark contrast to the real man. Outwardly, Stosuy is big and burly, walking around Brooklyn with a giant beard and covered in tattoos, many of which depict notable moments in his life. In person, the veteran Writer of a Thousand Outlets is a gentler man, telling compelling stories about wilder times and his kids' obsession with the Misfits in a soft, pensive voice.

My own story with Stosuy started many years ago, when he and I booked shows together as part of a series for his Show No Mercy column at Pitchfork. Many of our choices were odd and avant-garde: bands like Keelhaul and Anal Cunt, which appealed to a select devoted few. Over the years, due to a shared taste in heavy and outer music, we shared moments at a zillion gigs and commiserated over publishing industry woes. At this point, it could be close to a decade. During that time, he's gone from Pitchfork columnist to editor at Stereogum to Pitchfork editor, and now he begins a new venture: The Creative Independent, focused on art and artists. It launches in two weeks.

Stosuy also wears several different hats, one of which is curator of Basilica Soundscape in Hudson, N.Y., now in its fourth year. Stosuy and co. famously book bands across genres and couple them with exciting visual art and food, in an atmosphere that is unique to the festival. This year's iteration kicks off on September 16 and ends September 18. Tickets are still available.

With the site about to start and Soundscape right around the corner, I spoke with Stosuy about the ideas behind Basilica, his move to The Creative Independent, and the state of writing and journalism in 2016. The results of our conversation are below.

The most interesting thing about Basilica — besides where it takes place and the overall independent spirit of it — is the scattershot booking. Do you say to yourself, "I want to have this many bands that will represent this style of music"? A lot of it seems like it’s in a rock, sort of free realm.

It’s organic. Often each year will have one bigger band that I want to get; for instance, one year I wanted Swans, and the scheduling didn’t work, so then we got them the next year. Swans are the first band we booked that year. I kind of wanted to build it around Swans, or off them in a way — things that make sense with them, but aren’t obvious. Each year we have a visual artist, so the year before that I asked my friend Matthew Barney to be the visual artist, and he and I always had this idea, like, let’s have four bands playing at the same time and try to conduct them in some way. So, we chose four bands that would make sense in that configuration. That year we booked Pig Destroyer, before they had a bassist, so we booked Evian Christ to be the bass, kind of. Pig Destroyer has a male voice, so we booked Pharmakon, which has a female vocalist and also more bass, and then Julianna Barwick, who also became another singer. We put that together since it made sense; that’s how we booked that year.

Everyone involved that year had a really tight conceptual connection, but also on a practical level, these four bands sound cool together! They also played separate sets. That’s how that came about; that was very specific. For a while, we had a thing where Brian [DeRan] would do one day and I would do the other day, and two years ago we shifted that, doing the whole weekend together. Brian would always joke like, “Here’s the dark lord day.” He lives in L.A. — in the desert now, in fact — so he’s out there painting in the desert and making ceramics. He’s into psychedelia and stuff. He also owns Ottobar in Baltimore, and he comes from a hardcore background; he’s friends with the Lungfish guys and all that stuff. He has a heavy aspect, too, but in recent years he’s more into psychedelia and whenever there’s a harpist. When we had the gamelan band, that was Brian’s doing.

Once we have a couple bands in place, we like keeping it varied and interesting. This year, I realized there is a lot of instrumental stuff, and even if they have a voice, it’s very spare, or the music itself is super spare. Bell Witch, obviously, has vocals, but there are large parts of it where it is very spare music. There’s a lot of that happening this year, more so than past years. One year, I remember it was very focused on voice, it felt; this year, it feels like it’s lack of voice, in a way, even with Wolves in the Throne Room. Wolves have vocals, obviously, but also large chunks of riffing and music.

We don’t have any quota or agenda of “let’s have this many bands” or this many kind of bands; it just kind of organically happens. Brian and I will just start adding names on Basecamp. We’ll go back and forth, and then Tony [Stone] and Melissa [Auf der Maur] will weigh in and say, “Yeah what about this?” It becomes this back and forth kind of thing, and then we start kind of chiseling it out. We’ll often be patient; we won’t ask a bunch of people at once. We’ll wait so we make sure we don’t make the mistake of asking too many and then being like, "Oh shit, now we don’t have the right kind of vision for it." It’s less like a festival like Coachella where you can imagine it’s just like, here are the bands that are touring right now, or reuniting, so let’s book them. It’s much smaller, so each band we have to really carefully think about and each of us have to sign off on — one wrong band could screw up the flow of that day. So, it’s a very collaborative back-and-forth kind of a thing.

This year just ended up being heavier. We added Cobalt towards the end. The other people hadn’t heard Cobalt yet, and I was like, "Yeah, they happen to be available." I love that record, and they just make sense; then Brian listened to it and was like, "Holy shit, this is amazing!" He was into the riffs and thinking, "Wow, this is pushing us more into the metal realm than we ever have," but they kind of just made perfect sense for the bill.

I think that’s one of the most interesting thing about Basilica: You package visual art and all these different facets. When you go to a traditional festival, you have your funnel cakes, you have your drinks. Maybe there will be some bullshit installation, but there is a lot more care put into it, more thought.

The idea behind it was that if you go to Coachella or something, there will be an art component to it — no offense to Burning Man — where you get more of a spectacle than actual art. Wow! There’s this giant sunflower! It’s something that people think looks cool, but is maybe not that interesting beyond the surface. So, we were like, "Let’s try to get real visual artists who are respected, working contemporary artists, and try to get them to do stuff that makes sense for the space."

There’s always this thing with festivals, like, "Let’s get the perfect artists!" But then the food sucks. "Let’s get the perfect bands," but then the food and visual art suck. Wouldn’t the visual artists also care about the food? Each year, Melissa handles the food side of things where she’ll be very careful about the food trucks she gets, like this is the organic gelato truck, this is the local farm-to-table place. There was also a chef on hand and a kitchen.

The idea is just that because of the size of the building — and people have asked why we don’t do stages outside — we are being hemmed in; that way, we’re never tempted to make it bigger than it is. It always stays this smallish kind of event, with about 1,200 people a day, that’s it. Not that that is small, but as far as a festival, it’s pretty small. It’s just the idea of never moving beyond that, never putting a stage outside, never being tempted to take it to the next level and book Flaming Lips or something horrible. This way, we can kind of just keep it steady and the same ethos that we started with. For us, like last year, Haxan Cloak closed out the last day, and that was packed in there and people were going crazy, and I was thinking, "I’m happy to have a festival where Haxan Cloak is considered big enough to be the guy that fills the room at the end of the night and plays this really heavy, abstract set with a bunch of smoke and incense." That was how it closed out, versus, “We need to have Outkast reunite,” or something. It felt like much more of an honest way of doing a show.

That’s very interesting. You guys aren’t concerned with growing. It’s more about maintaining and keeping a thread running through all the years.

Yeah, for me, I always feel like I have the benefit of having a day job, so it’s not like I’m doing Basilica to make money. Every year, we essentially break even. If it were a business, it would be a horribly run business; but because we all have the other stuff we do, we can do this event as long as we’re not losing money, and we’re happy to keep doing it. All the money is coming from ticket sales. There’s the bar and stuff like that, but all the advance money is coming from ticket sales. Then we have the booze people buy, and that’s basically it. That’s where we’re generating the money, and paying the bands, paying the staff to be there; you know, just dealing with the upkeep of the venue stuff.

The priority is just to keep it interesting, and I think if we did make it bigger, then we have to get sponsors. If we did it bigger, we would have to raise ticket prices and discount tickets for students and senior citizens. This allows us to keep it at a pace we’re comfortable with, and even when it seems like, "Oh shit, we haven’t made our money back yet," then suddenly tickets will pick up. There’s always that kind of thing where it’s like each ticket we sell, we think, "All right, cool, we sold another ticket." Which I kind of like. It keeps you more focused on the event itself, and you can’t tune out; you’re just there thinking about it. For me, I don’t have any interest in blowing it up into this gigantic thing, you know?

How did the Pitchfork tie-in and now The Creative Independent tie-in differ, outside of you, of course?

Brian had gone to this event Matthew Barney and I had done, and he just thought, "Wow, this is someone who kind of fits the bill of what they want." So, he met with me one day and kind of pitched the idea. That’s when we did that first one with Liturgy, the super last-minute one. It’s something I would have done regardless; it wasn’t pitched to me like, “Hey, could you have Pitchfork do this?” It was like, “Hey, do you want to do this thing?” Because I worked at Pitchfork, it was cool to loop in Pitchfork and benefit from that media spotlight, so there was always an association with Pitchfork. They helped to promote it, do news stories about it, tweet it, that kind of thing. Plus we used the amazing graphic design of Mike Renaud, who really created an amazing look and feel for Basilica Soundscape.

When I went to The Creative Independent, it just came with me. I think The Creative Independent, the way it’s structured, it formatted Basilica better. Each year we have people read; we always have the reading series. We’ve had visual art, we’ve had [a] film component. This year, we had a Tony Conrad series of films that my friend David and I curated together; he and I were students at CUNY Buffalo, so it really fits the idea of "creative independent." Cole [Rachel] and I, we were going to do a conversation series there; he’s interviewing Genesis, I’m interviewing Sarah [Taylor] from Youth Code and Amber Tamblyn, who is a poet and is curating, so we’re going to have that series. In the past, Pitchfork helped get the word out, but this year it just made sense. Like, “Hey, we’re doing all this stuff, the site has some interviews; let’s do some interviews while we’re there with people we would cover anyway.” It definitely integrated itself in that way, in a very organic way.

This year, it’s Creative Independent, which makes total sense to me. It’s going to be helpful, too, as the site grows; it’s one of these things where maybe we do even have more of a curatorial eye toward things that connect to the site also. This year, it’s tricky because we’re essentially launching at the same time, right after Basilica happens. The site is not even a site yet.

Do you feel like The Creative Independent is freeing as far as your subjects are concerned? Did you make a conscious decision to get away from music specifically, like maybe you’ve been in music for too long, to vary your interests? Why did you make that move?

We’re definitely interviewing musicians still; other people, too. I got kind of sick of the music industry itself. I got sick of things like SXSW, where basically it was like me and a bunch of people standing around drinking beer at 1 p.m. watching a band, or some sponsored showcase, and I was like, "This is kind of exhausting." But also I’d always been interested in these other things; I always have side projects where I would do art with friends or collaborate on installations with people. I went to grad school for literature, so I always felt like, “Man, I have all these other interests, but I’m just writing about music,” or “I’m only doing this music stuff.” It felt nice to take a step back, in a way.

I still love music, but I didn’t like all the machinery around it, so now I get to talk to artists and musicians and have interesting conversations with them, but I’m not worried over album releases. We’re not looking to interview people in their off-cycle; we can just interview them whenever about specific ideas related to stuff like creativity in general, or creating things, or making things. It’s less like, “Hey, Angel Olsen, let’s talk about your new record,” but more like, “How did you go about this?” It becomes a separate conversation.

It’s been nice. It frees us up from not having to be the first at anything, but everything we do can be an evergreen interview, in a way. I can still do music things, which I love, but I don’t have to worry about saying that they’ll give us this interview, but would you also like to post this mp3 for this other band? That kind of thing we can just duck out of, because it’s much more like we can interview people however [we want]; we don’t have to rush around.

There was this really amazing period where nobody knew what Creative Independent was, and I left Pitchfork and it was announced I was going to Kickstarter and doing this thing, whatever it was. My inbox was empty, and I was really relishing that moment, where people that I was friends with were writing me emails that I really had to respond to, and as it became clearer what it was and it got to the point where it wasn’t Pitchfork: thousands of emails a day and you just felt like you were drowning constantly. There was even a moment I remember when I left Pitchfork and it wasn’t announced yet what I was doing, and I passed this publicist that would always talk me up, and I gave him a wave and he was sort of like, “Yeah, whatever.” I thought, “This is great. I’ve reached this moment where I’m not catnip to publicists anymore.”

Was the idea for The Creative Independent yours? Or did it come from Kickstarter?

It was something that kind of developed where I’d spoken with Yancey [Strickler], who is one of the people who started Kickstarter pretty randomly, who I’ve known for years. He actually worked at Pitchfork briefly a long time ago. Their office was a block away from where Pitchfork used to be, which is now my office. I was just getting coffee when Yancey came in and he had this idea — a general, vague idea — of what it might be, and then we talked more about it. I said, "This actually sounds like something that I would want to do," then we started talking more seriously about it. He definitely had an idea, and it’s been great. I’ll meet with Yancey once a week, then I’ll meet Perry [Chen] like once a month to tell him what I’m doing, and often Perry’s advice is something like, "Hey, there’s this interesting conceptual artist from the '60s — he’d be cool to interview." Stuff like that, that’s very much on the line of what I’m interested in doing anyway.

Before I took the job, they said we can grow this thing organically, that has its own arc that kind of just takes time and then becomes something. They stuck to that, which has been cool. Also, the whole rollout — I said I wanted to be really mysterious at first and really let it be this slow thing that just happens. They were totally cool with that and let me do that. Initially, they asked me what I’d like the design page to look like when the sign-up page comes up, and I said just black text with a white background. They’ve been very honest about every aspect, which has been great. They’re really supportive.

What do you think about the state of journalism?

Everything is in a weird place where it’s like an echo chamber in a lot of ways. Everyone is writing about the same stuff, fighting over the same piece of the pie. You’ll read 10 interviews with the same person that are all slightly different, but slightly the same.

I think you could debate that it looked kind of similar in print years ago.

Yeah. I guess there were fewer print things, in a way. Fewer specialized things, so maybe people weren’t covering the same things as much, but I think there’s a lot of great stuff out there, too. There’s a lot of insightful pieces. I think there’s a lot of young people who are a lot smarter than I was when I was younger. People in their early 20s who are already doing amazing writing; when I was in my early 20s, I worked in a gas station. There are definitely people who are getting better writing jobs at a really young age, which is interesting to see.

I think the thing that’s weird is when things kind of move away from the writing — the New York Times had that thing recently where they cut all the local coverage for theaters and galleries and stuff. People have left the Times, like Ben Ratliff, who is an amazing writer and was the reason that a lot of the stuff that I booked even got covered in the Times. Him being gone, a lot of people seem to be ... a lot of these places seem to have rotating casts of people they hadn’t before. I assume a lot of people are changing the way they cover things. More things seem to be based on algorithms or something, people giving less trust to the writers, saying we need to have more think pieces, etc. That’s the dark side of it.

On the positive side, way more people seem to be writing, more people have access to things at a young age, so people are becoming better writers early on; more interesting thoughts out there. There’s definitely a positive and a negative to it. You get a lot of great voices and a lot of people who are just trying to rush things up quickly. A lot of news stories that aren’t really news stories.

Do you feel like there are a lot of great writers out there who aren’t necessarily well-versed in music?

Yeah. There’s a lot of people at a young age who just don’t know the history. One thing I’ve found from people who learn a lot on the internet is that you don’t have the connections down, because you’ve read stuff on Wikipedia or you weren’t really around in the '90s, so you have this idea that this one band was someone they’re actually not. They’ve just been spun by their publicist after the fact; that kind of thing happens.

You also have people who are amazing writers who somehow don’t fit the current speed or tenor of things; they end up having full-time writing jobs, and it’s like, what the hell! How does that person have that job? One of those people was Cole, who I hired for TCI. He was bartending and also freelancing, but to me it was like, "Wow, this guy is such a great interviewer and such a great writer; how is he not a full-time writer?" He’d taken time to write a couple books of poetry and did other things, and he was just on a different path.

I think a lot of people now are getting more professionalized more quickly; before they even leave college, they’re getting a writing job. It was rarer back in the day, and now it’s not so rare. It’s a good thing and a bad thing; some people are really great. For me, I’m really glad I had my young writing out the spotlight, because I look back on it and I’m like, oof. I feel glad that I had that grace period, where people weren’t reading my stuff outside of a few friends..

One hundred percent. Do you feel like the way the internet works rewards good writing?

More eyes are going to be online than on print, so even if you have an amazing article that wins some journalism award, more eyes are going to be on a piece about Kanye’s fashion show. The trick is, when those things happen, whenever people post a similar variation on that theme, whoever gets there first is the one who is gonna get the most eyes. That’s the part of it that I find fairly boring: Let's be the first one to say this basic thing before everyone else says the same basic thing. It just becomes 800 articles on this weird, small minor thing, and it becomes a big thing. Its like when you see those cartoons and a bunch of smaller fish are herding together into the form of a larger fish. A lot of these stories are smaller fish that somehow gather force and become much bigger than they actually are. In reality, it’s the smallest thing in the world.

The internet has this whole outrage thing, too, where people get outraged about things that they shouldn’t, and seemingly complacent about things where you should be outraged. It’s a weird mix.

More From CLRVYNT