Merchandise’s ‘Corpse’ Is Wired for Violence, Not Love

2016 may have been a pretty shitty year, but it gave us plenty of great music. With critics everywhere beginning to roll out their best-of lists, we're starting to see a lot of the same names (and rightfully so): Beyoncé, Frank Ocean, Chance the Rapper, Radiohead, Bon Iver and the like. In the interest of diversity and due diligence — and out of respect for the underdogs — we here at CLRVYNT are taking this month to honor some releases you may have overlooked.

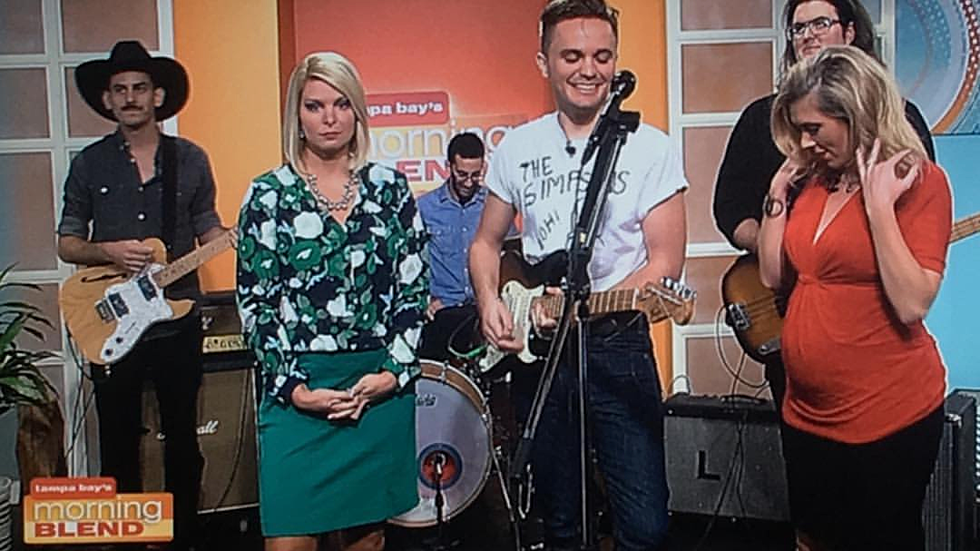

This September, Tampa firebrands Merchandise quietly released A Corpse Wired for Sound, their most ambitious, expansive album to date — a spacious sound mired in misery and disillusionment, as frontman Carson Cox explained in a phone chat later that month. The musician delved into a wide range of topics over the course of our hour-long conversation: the new album (and the closetful of skeletons that inspired it), his hardcore band Death Index (who released a record earlier this year), his rapidly gentrifying hometown of Tampa and much more.

One of the recurring aspects in profiles of your band is how the punk community were kind of assholes once you started to branch out and embrace melody. Are they still giving you shit? You put out the Death Index record, which in some ways probably made them put their foot in their mouth.

We put out an LP, but it was like giving a demo tape to a couple of people. We did a Europe tour and an American tour. And I still knew all the people who were gonna come out to it. I don’t know, I still don’t really understand … I still feel like we're alone in the crowd when we’re putting out something. Death Index, that definitely got some press and people found it, but I think it's more subversive and more against the grain than whatever punk bands I’ve heard.

I think you could say the same for this record, too. That's the first thing that caught me off guard about it. It’s another kind of scorched-earth approach. Was there a point where you were just kind of like, "Fuck this, let’s go in a new direction"?

I mean, that’s every day. Every day I wake up and I’m like, it’s time for a new direction, or it's time for a new city, or it's time for a new name, it’s time for a new idea. We recorded a lot. I wrote like 30 songs, and we picked nine. “Silence” was supposed to be on Children of Desire, but the recording of it was too lo-fi, and “I Will Not Sleep Here” was the same thing. That was gonna be on Totale Night or maybe even the first record, and we just couldn’t do it. And when we went to the studio in Italy, those things came together, and the other 20 songs or whatever didn’t bind the same way. So, we just put 'em together that way.

I was just into working in a kind of a style. The idea of throwing Naked Lunch on the floor and a bunch of different fragments and putting it all together. That idea of working in an abstract way. While I was living in New York, I’d go to the Met and just pay a penny to see Jackson Pollock. Going to see work paintings that I thought resonated with me that seemed to have a disconnect with being in a gallery — seeing Jackson Pollock and then also seeing Jim Shaw from Destroy All Monsters' stuff, and being like this disconnect with the things that all resonated with me. This is like an anti-concept record. I’ve been reading some reviews and people are like, “Oh, they’re really good at writing love songs again.” And I’m like, "There isn’t a single love song on the record." [Laughs]

This record is all about violence. It isn’t about love. Most of Sound was about some brutal closure I had this year with the idea of this person I thought I loved for years and years, and coming back to it and realizing that all these fragmented memories I had of this person was actually one that I had fabricated in my mind. And when I started talking to them again, I had all this closure and realized there was nothing special there. This idea of the beauty that you see in the world is actually in you, and it's your interpretation of it. The beauty and the love that I saw in this person was just an illusion. It’s just like, everything falling apart. “End of the Week” is an extremely deconstructed song. Even the chorus is a cut-up of the verse. And the line from the chorus is not me singing; it’s a phrase cut in half, but it sounds like I’m singing a phrase. I wanted to construct something in a [William S.] Burroughs style, and it ended up being a single. I don’t know — to me, it has nothing to do with love. It’s more anti-concept, anti-love. “Flower of Sex,” maybe you could call it a love song. But I feel like it’s so violent. It’s just from reading [J.G.] Ballard and seeing his obsession with violence, and the mirror that violence is, and how people read into it. What a violent image can do has a real moralizing effect on me. I’m not a violent person at all. I’m extremely non-violent. There is a time for violence; whether or not I think I’m a violent person, there is a time for everything in human nature. The construction of this is so anti-rock, but we ended up with rock songs, in some weird way. I guess I just know too much about the composition.

"Anti-rock" is an interesting term. One of the things that struck me most about “Lonesome Sound” is how the main hook — which I think is the catchiest thing you've ever written — shows up twice. I kept expecting one more by the end of the song. Was that an intentional omission? "People are expecting this, but we’re gonna give them this freak-out with guitars"?c

I feel like that composition started in Italy, and we really changed it so much in Florida that, by the time we got to Florida, it became this shredded, distorted thing. There was scratch stuff that we left on it because we felt like it was just cool. For some reason, that song always reminds me of Gun Outfit. We’re touring with them in the West Coast, and they’ve been one of our favorite bands forever, and we’ve been playing shows with them since 2008. [Laughs] Like forever. So, I don’t know — there’s a weird Western thing to the whole structure. And a folk idea of pausing, and the way that the phrases fall. It’s a combination of noise and electronics and this weird compositional thing. It just came out of nowhere, and I guess it's a new thing for us.

When we finished [the song], I was like, “Yeah, this sounds like us, I guess.” We were changing stuff so much that, by the time we got done, I was like, “Wow, this actually sounds like us.” We went to the studio, and I thought it would come out completely different. I feel like this folk thing has always been in the band. I feel like nothing was traditional. I just wrote. Wrote, wrote, wrote, wrote, wrote. Everything that came out, I tried to make it like a Ouija board, where it would kind of like resolve in some way. And Dave [Vassalotti, guitarist], obviously, his influence on the record and the guitar style is super important. He doesn’t write the way that I do. I love technology and I love using weird, generative ways to make music. His idea is very classical. He’s way more about composing in his mind and on paper and have it all come out in the performance, whereas I like bits of electronic stuff and fragments of stuff. It’s a lot like scrapbooking, where you have all these things and look at them and whatever has an impact. I don’t know. It was a very strenuous record to make out of the newness of working in a studio and traveling and making part of the record outside of Florida.

Was this your first time working with an outside producer? The last record was self-produced, right?

Yeah, we produced everything. The only thing was that Gareth Jones mixed it. He did a really cool job. He recorded some of my favorite Einstürzende Neubauten records and Tuxedomoon and Nick Cave and Depeche Mode. He’s sort of a hero. But he really didn’t produce anything, because he’s in London, and we did all the production in Tampa. And we’d just go back and forth on the mixes. His touch is on certain songs, like “End of the Week” and “Shadow of the Truth,” and these big industrial songs. And for sure he had an impact on the whole record.

But I don’t know — it wasn’t so much of a production job. It was like he became a part of the band. There were even songs that didn’t make it to the record where he played drums and I would play bass and Dave would play guitar. He didn’t have a normal production role, because we were living together. I don’t think we could ever really work with a producer that wasn’t like our friend, our somebody that we had a crazy connection with. And I don’t know — it was super cool. He’s gonna be working sound for us in Europe, and be on tour with us. And I’m trying to convince him to play guitar at the soundboard. Play keyboard or guitar, do all these weird things, coming from nowhere, Mission of Burma-style. Tape loop stuff. Recording stuff and sending it back out and doing weird shit with it. We’ll see. Depending on how high we get is really the question.

Starting over is a big theme on this record. On "Right Back to the Start," you talk about "collecting seeds." Are those "seeds" ideas? People?

Everything. I mean, it's definitely an image for this sort of essence of my life. The essence of my family and my personal history and my musical side. I feel like when I left Florida, I left so much, but I felt like I had so little. And I feel like I’ve gained so many possessions in my life in Florida. When I left, I just had two suitcases. And it was like, the possessions didn’t really fucking count for anything, you know? It’s just shit you accumulate. You can plan to save in many ways. You can start growing a life, whether it's a family or it's a career or whatever. It really felt like it was just over in Florida in that way. And then it also coincided with, yeah, the fucking end times. The evangelical, political fucking destruction of society there. And everyone being totally comfortable and complacent with it. It was losing my personal life, but also, like, everything. The whole package. [Laughs] And in that way, personally, it was a new beginning, but also in general, the neighborhood I grew up in is another neighborhood that’s fallen victim to gentrification. We were just white trash. It was right down the street from the projects. And it’s all changing. When I walk around that part of town, it doesn’t exist anymore. The line about my grandfather ...

I was about to bring that up.

I’m talking about his neighborhood, I’m talking about his life, because his life was based around not his family, but the actual neighborhood. Everybody would come by his house to eat Spanish bean soup. And he’d make a giant pork roast. Obviously, he wouldn’t cook that stuff when I was vegan, but he would still cook for me when he was still alive. And the way of life was around the dinner table. Even if we were playing rummy and everyone was drinking scotch, you sat around the dinner table, you had conversations.

That was my life growing up. And that whole side of the family has disintegrated. And on top of that, they’re building oxygen bars in that neighborhood. It’s super sad to watch. Of course it didn’t have any monetary value, and developers don’t give a shit about sentiment. To me, that was a really important place, but it was just over, you know? It’s fine. It’s what happens. It’s the cycle of life, it’s the cycle of how everything goes down. And you can’t fight it. It’s just, whatever, start over. Go somewhere else. And that’s just what I did. It’s very bizarre, and I feel like I don’t really have a home anymore in Florida. But I don’t really live anywhere. I’m just as comfortable in Berlin as anyplace. It’s definitely bizarre. But it’s just part of getting older. It happens to everybody. I don’t want to sentimentalize it or anything. It was just a realization that was powerful enough to write a song about.

You’re kind of a ramblin’ man. Do you have any place that you would consider your home? The other thing about the record — there are so many themes about things being liminal. Nothing really being there. What does ground you?

It’s more about inner space than tangible space. The tangible side of life is more fleeting as I get older. And it’s not just the places that I was familiar with changing. It’s just my connection with my friends and my family that I still have. That is really the most grounding thing. It’s been a long time. Whenever I start touring, I see people. Just last night, I saw some friends in Atlanta that I consider more than friends. They’re family to me. And it's the same with my friends in Arizona or my friends in Berlin. I think they ground me because I’ve developed this life on the road. It’s more about that connection with them than the physical sort of space. I connect more with that; it feels more real than the tangible. It’s always kind of been that way. And now, with Florida becoming totally overrun with this sort of development and destruction of whatever is natural there, it just accelerated that practice. I can walk down Broadway and feel just as at home as anywhere else.

One thing a lot of people haven’t talked about is how you’ve been doing a lot of work with Wharf Cat. I was wondering if you have any productions that you have on deck?

There are few other records that I don’t know when they’re gonna come out, because they’re basically produced and pressed. We just have to figure out how they’re coming out and when they should come out. But a lot of big things in the future with Wharf Cat. Stuff that I’ve played on, stuff that I’ve produced directly. And they really were my family when I was living in New York for the past six months, you know. They totally embraced the creative side of whatever we’re doing. And obviously it's a label and they want to make money and they want to do all the stuff, but they really go after creative projects that I’m into that don’t fall under any scene or category, and, yeah, it's not even just like this next year. The next five years, I would say, a lot of the big stuff that I’ve been working on, creative stuff, is either coming out through Wharf Cat or [somebody] I have a direct relationship with.

Do you plan to do anything else with Death Index?

Yeah, we’re actually working on a second record. And, again, it's gonna be weird and fucked up and dark. We recorded some when I was in Italy. We recorded a bunch of pipes and big fucking metal things. Just smashing them and breaking glass. So, the next record is gonna be pretty heavy and weird.

Is the muse gonna move you to put out any of those two dozen outtakes that didn't make the cut for?

Maybe! Some of them are so electronic that they just don’t fit on the record. And some of them are really garage-y and shitty-sounding. I would like to do a B-sides comp. I think that’d be cool. But again, we’ll see. So much effort goes into producing LPs. And people don’t really buy records anymore. They just stream it. So, if we put it out, maybe we’ll just put it out for free or online. We just have to figure out how to do it.

More From CLRVYNT